Many years back to sell newspapers, sensational headlines were conceived to get immediate attention so people would buy the paper. It went like this “Strike! Innovation is on strike! Read all about it” Today innovation is actually on strike! Just take a look at this:

A strike of declining investment, of a lack of confidence, of not sharing in the belief innovation offers a solution to our continued problems of wealth creation, of economic growth, of galvanizing society.

So for many, innovation is actually on strike, we are not investing as we should according to a series of reports and analysis, focusing specifically on the UK economy, sponsored by Nesta. Nesta is the UK’s innovation foundation and they help people and organisations bring great ideas to life.

They do this by providing investments and grants and mobilising research, networks and skills. They operate independently but are very central in shaping innovation thinking.

You can “read all about it” through these links offered, firstly an Executive Summary and the downloading the full report from their site.

I offer a fairly extensive set of ‘extracts’ below, so read on:

Already a lost decade of innovation has occurred

According to Nesta “The UK economy has experienced a ‘lost decade’ of innovation, with new evidence showing that businesses had a crisis of confidence in the 2000s, prioritising cash and concrete over investment in innovation”.

* Nesta’s latest Innovation Index released back in 2012 showed that investment in innovation by British businesses has fallen (or collapsed) by £24bn since the recession began and has not recovered. This is five times the amount the Government spends each year on science and technology research.

* Recently a further view on innovation was expressed by Nesta in mid-March 2013 on how to use the Government’s purchasing power to boost Britain’s most innovative businesses, arguing there is a continued and urgent concern on how to get Britain’s businesses investing in innovation again.

Some major points summarized here

I cannot provide proper justice to these extensive reports or to all the contributors that make up its worth but let me attempt to pull out of these reports some headlines that seem to me the real underlying issues of why the UK, and many others, are in this period of innovation stagnation.

Nesta produces a highly valued innovation index for the UK, this showed in its third review

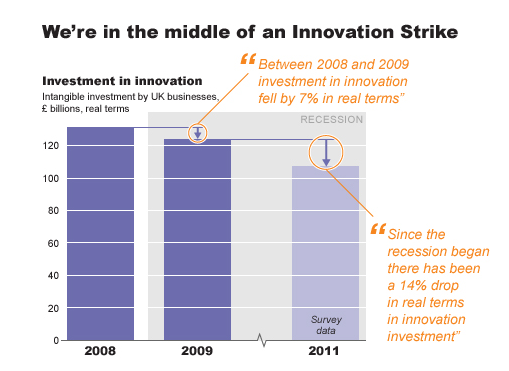

- Innovation investment fell by 7% or £7.4bn between 2008 and 2009, as the recession began

- A further fall of 14%, or £17bn, from 2009 to 2011, according to a survey of 1,200 businesses

- After rising steadily from 1990 to 2000, innovation stagnated from 2000-2008 at 12% of private sector output

With a decline of £24bn, since the credit crunch in 2008, it is interesting that even in the period between 2000 to 2007 businesses investment in innovation had levelled off. Investments in fixed assets fell and became increasingly dominated by bricks and mortar at the price of technology. Companies accumulated cash and concrete in the 2000s, far from the age of innovation.

There has been an increasing disconnect between the UK’s financial sector and investment in innovation and technology. The 2008 financial crisis has turned into the longest downturn in modern times.

We are seemingly caught between the two sides of an argument, Plan A for recovery based on austerity or Plan B based on stimulus. We see the continued consequences of the hardening push for austerity in nearly all the Mediterranean Countries, let alone the severity of the austerity part has continued consequences in the UK and the USA . As we debate this two dimension view there are crucial ways everyone is losing ground, especially to the developing world and its significant focus on its innovation activities.

Nesta argue for Plan I to be the ‘missing part’ for the UK to thrive as a productive, dynamic economy.

The report lays out in significant detail the areas of potential focus and why and what they can be achieved to reverse this set of trends on innovation investment and regain economic growth within the UK.

Firstly dealing with the question of innovation

- The ability to turn ideas into useful new products, services and ways of doing things is the wellspring of prosperity for any developed country

- The companies that invest most in innovation tend to grow faster than ones that don’t; and the countries that invest most in innovation do as well

- Nor is it a coincidence that many of the nation’s doing best today in innovation have articulated a clear vision of where they think their future wealth and jobs will come from

- Countries as diverse as Korea and Finland, Israel and Singapore have sustained a mood of optimism and possibility through the crisis, and given business a sense of the future gains that make investment today worthwhile.

A growing reality or a self-preservation attitude still prevails.

- Unfortunately the current economic debate in the UK has pushed innovation and questions of long–term growth to the margins

- But if we want to take advantage of the opportunities on offer in the next decade from new technologies, new markets, and new ways of doing things, we have to face up to the gaps, the failings and the many ways in which institutions and markets aren’t well designed to make the most of new ideas. They stay stuck in the past.

- It is hard to calculate precisely the size of the gap, but some of the analysis that follows suggests that in the UK, they may be under–investing in innovation to the tune of £38 billion a year.

- Transformation from industrial decay shows that change for the better can happen relatively quickly where there is the will. Currently we leave to many as “walking dead” and badly under support those in finance and resources required that show the way forward to ‘regenerate’.

The prize according to Nesta’s report is what innovation still offers us

- First, the continuing advance of information technology is showing no signs of slowing down. Moore’s, Metcalfe’s and Gilder’s ‘laws’, which predict that processing power, bandwidth and network connectivity will increase exponentially over time, still appear to be in full force and can open up a dizzying range of possibilities

- The huge potential of ICT is just one aspect of innovation. Other technological developments, from new advances in life sciences to the emerging disciplines of nanotechnology could have just as large an effect.

- During this phase it may be the ability to integrate different technologies that will be critical — from genomics and proteomics to bioengineering. New materials, including graphene and other carbon structures, may lead to dramatic breakthroughs in manufacturing.

- Social innovations also offer great potential. The wastefulness, in both human and financial terms, of the way we run our healthcare systems, the way we care for old people, and the way we treat the most excluded in society, is huge

- The right social innovations could unlock as much value as many great social innovations did in the nineteenth century. During past periods of rapid change, like the mid–to–late nineteenth century, radical social innovation and reform proved essential for the full deployment of technological innovations, from industrialisation to the railways. The same is very likely to be true as the world gropes for a new approach to growth.

Most of these innovations will create benefits not just for those who develop and commercialize them, but also for those that can effectively deploy them, and build new services and businesses around them.

The poor state of the UK innovation system needs rethinking

The interplay of resources, people, ideas and markets in which innovation happens — much isn’t working well according to the report. What can be improved?

There are three broad ways in which the innovative capacity of the UK can be improved:

- Investment: increasing how much the UK invests in innovation

- Systems: upgrading the system of innovation so that these investments go further, including greater demand

- People: changing the underlying cultures and skill sets to be more innovation– friendly

Making the innovation system work better

The second factor suggested, that holds back the UK’s ability to innovate, is the structure of their innovation system and is worth one additional comment — it is the combination of the involved organisations, their links and forms that determine how new ideas become reality. For over a hundred years, commentators have noticed a contrast in the UK between the world of ideas and the world of implementation– what a lovely observation that is!

Designing an innovation policy

So within the report there are many policy suggestions but the aspect that stands out for me come in the way the Nesta’s reports suggest four design principles for effective policy development

A design that involves arranging fundamental elements according to a few overarching rules or ‘design principles’, and then they suggest we all furiously set about adapting and improving them in the light of experience. Keep it simple, effective but well focused.

The four are summarized here:

- Experimentation. Innovation is a risky business. Breakthroughs only come from a willingness to push at boundaries, to take risks, and, sometimes, to fail. What matters is not backing winning projects every time, but backing a good portfolio of projects. Experimentation is not easy, especially in an adversarial political system, that is often very risk adverse due to this. Risks need to be taken in the face of huge challenges like ageing or climate change, as well as in making the most of great new opportunities like the Internet of Things or synthetic biology.

- Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs are essential to an innovative economy: they don’t usually come up with ideas, but they do work out how to put ideas into practice. Entrepreneurship is also important to good innovation policy-making. The flip–side of an experimental innovation policy is the need for entrepreneurial leadership and challenge within the system. Entrepreneurial leadership within the system can be valuable. These kinds of entrepreneurial figures provide a valuable antidote to consensual policy that works primarily with incumbents.

- Openness. Good innovation policy cannot be made by government alone and certainly cannot be delivered solely through state bodies. Innovation flourishes when businesses, research organisations, and intermediaries such as standards bodies and trade bodies come together to identify and address major challenges. What is important though is government cannot rely simply on assembling interested groups – this risks capture by incumbents and vested interests, it needs a very open platforms where all can participate, working towards their goals but recognizing the essential need of all the diverse participates on the platforms.

- Ambition. Finally, innovation policy needs ambition, with the right mix of challenge and focus. Government’s power as a leader, as a customer and as a regulator matters as much as it’s narrow role as a supporter of research and development. Finland, Korea and Israel are all countries that have managed to make this a reality. In all cases, leadership has come from the top but been broadly based.

Making policy needs to guard against certain common present barriers

The process of making innovation policy must be future–focused. The value of foresight exercises are recommended which are not great at predicting the future but better at making those who undertake them recognise the future when it manifests itself

Policy also needs to be aligned. A frequent complaint made by foreign businesses looking to make major R&D investments in the UK is that government policy is poorly aligned: helping to orchestrate such things as land, planning, training, supply chain development, and links to universities

It seems UK innovation policy lags behind that of Germany and Japan for example, both of which use grand challenges as a way of organising and focusing innovative activity.

The report finishes the discussion section with this before it moves into specific proposals.

The endless public debates over responses to the economic crisis needs to change if we are to put in place a sustainable alternative to stagnation. We need business leaders who are willing to prioritise the case for innovation over other issues such as top rates of tax or regulation.

We need to use critical moments of choice, we need to restore faith and trust, we need to unlock this huge cash pile sitting on many organizations balance sheets.

And we need political leaders with a deeper understanding of innovation (at present only a tiny fraction have direct experience), and an appetite to advocate it. Innovation needs political and public advocacy and argument if it’s to be widely supported.

In summary

Nesta are a tireless champion of innovation. The whole understanding that if innovation stagnates so does the chance for recovery, for wealth creation and growth in jobs, and in our economic activity. We are not ‘stretching’ for a better future, we are sitting back waiting for the right ‘fundamentals’ to return.

They will not unless we decide to open up and reinvest in ‘things’ that have perhaps higher risk but contribute to changing today’s lack of dynamics.

This report might focus upon the UK but much of what it argues applies to most of the developed nations in Europe and North America.

We are told our corporations are awash with cash; our governments are strapped for revenue generation activities. Plan A requires austerity, Plan B needs stimulus but their balance requires what a Plan I can offer. To regain growth but at the same time manage what we have more wisely. We need to balance all three.

I can only recommend you spend some time on the Nesta web site and value, as I do, their focus on innovation in solutions, stimulating debates, conversations and well-structured reports.

They are one of the best sources to go, for appreciating the complexity of innovation and being able to “see” where innovation lies, at the heart of all our futures.